Books: Catalysts for Health Care Change

This work was first published in Hektoen International.

Some books are enlightening, others are influential, but precious few are transformative. Those rare books are catalysts for change that help propel society into a collective “ah ha” awakening. Think of Silent Spring,1 The Jungle,2 or The Feminine Mystique3 and their respective effect on environmental consciousness, food safety, and women’s independence.

There is no shortage of books on topics pertaining to the gargantuan U.S. healthcare industry: clinical treatment, affordability, quality, safety, organizational structures and infrastructures, and many more. Excluding publications on personal health and wellness-related issues, some books have helped shape, shift, and transform the colossal system in very different ways.

Entry and exit

We now have access to an abundance of information, both print and electronic, to help us prepare for birth and death, life’s entry and exit milestones; yet, that was not always the case.

Just a few decades ago, a woman having a baby in the hospital was treated much the same as one having a scheduled appendectomy: prepped, anesthetized, and alone in the delivery or operating suite (save the medical team), to awaken later in a recovery room.4

Childbirth without Fear; the Original Approach to Natural Childbirth paved the way for a vastly different kind of experience.5 Grantly Dick-Read wrote of childbirth, or labor and delivery as it is referred to in medical circles, as a natural process rather than a stark medical procedure. This book introduced breathing techniques and the partnership of a spouse or coach to help women deliver their babies without the hazards of general anesthesia and without the unmitigated pain of past generations.6 Concepts that were considered radical when the book was published in 1944, are now routine expectations that women have about childbirth, especially of pain management, natural techniques such as breathing, and the active involvement of their spouse and/or other loved ones in the delivery process.7

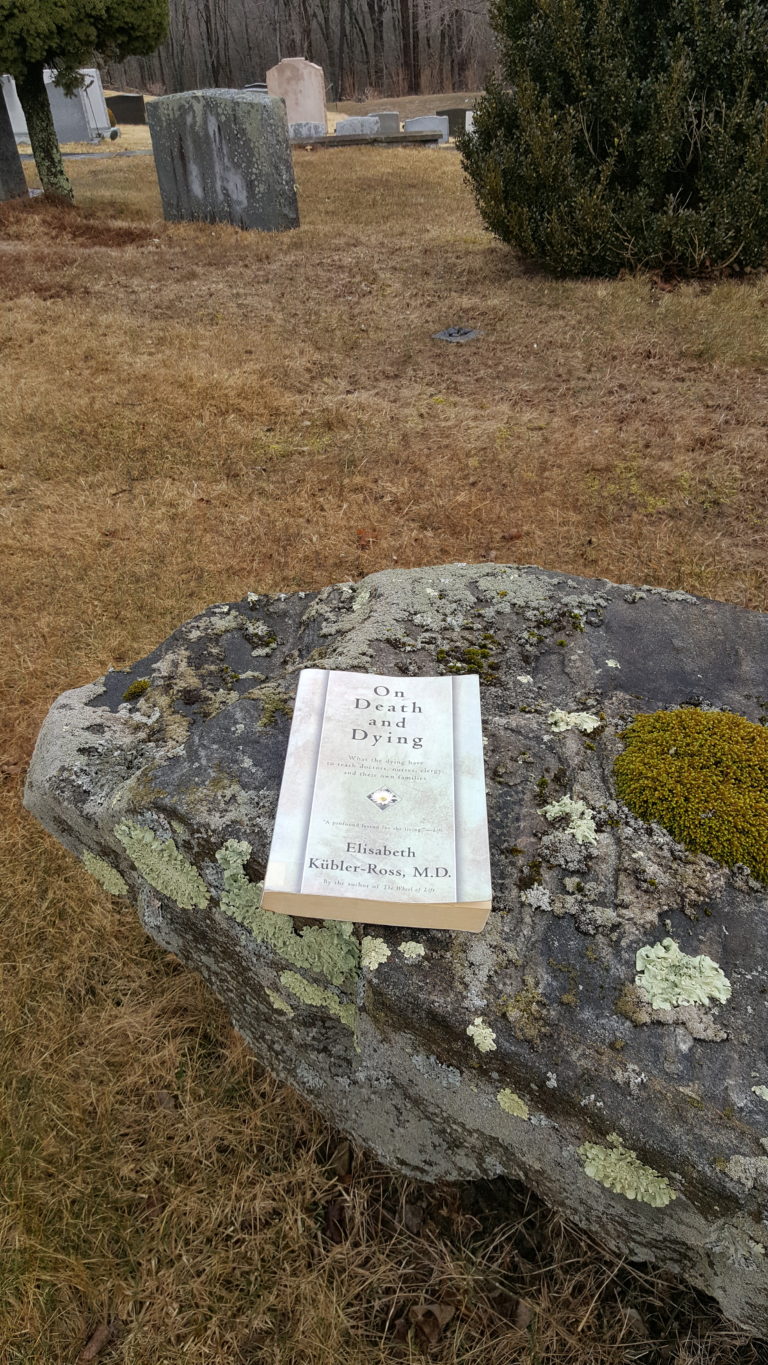

Another book tackled a taboo topic at the other side of life’s spectrum—death. In 1969, it was common practice to deny the nature of terminally ill patients’ conditions and keep that information from them. On Death and Dying helped change that.8

Seeking to interview dying patients, author Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and her colleagues initially met stubborn resistance from the medical community.9 Whether the physicians were protecting their patients or in denial about the prognosis is unclear, but Kübler-Ross eventually gained access and those patient and family insights helped inform the now widely-described and accepted stages we recognize in loss: Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance.10 A seminal work, On Death and Dying11 “cracked open the door of death’s proverbial closet” and paved the way for the acceptance and integration of many end-of-life programs and resources like hospice and palliative care.12

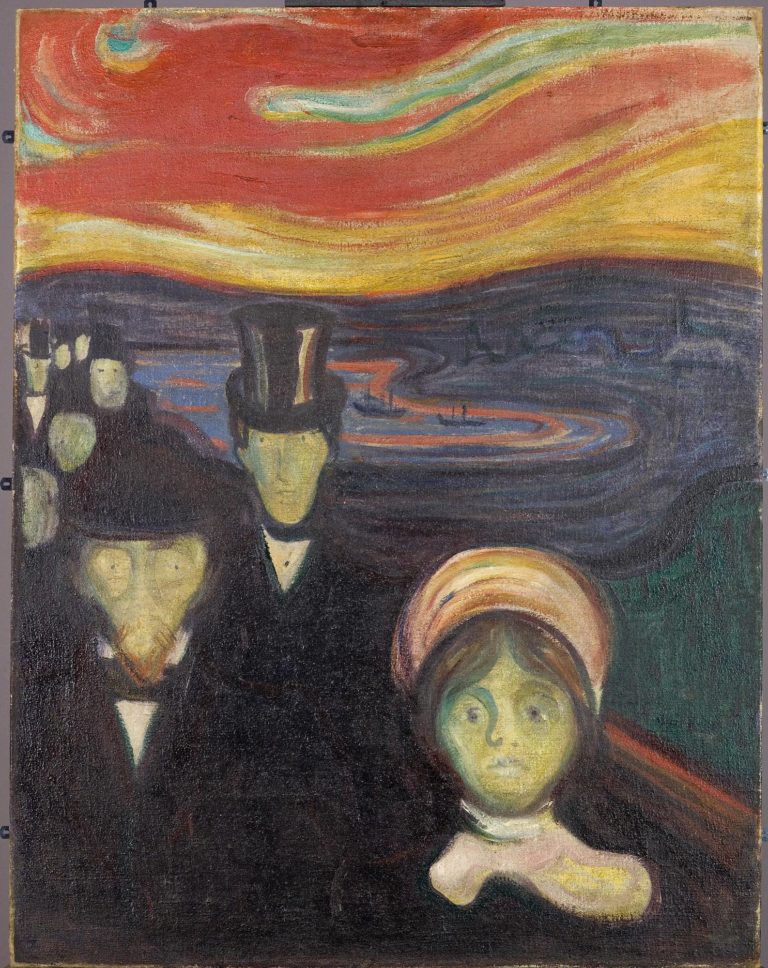

Truth in fiction

Not all transformational works are non-fiction; the truth contained in stories can be powerful forces. Author and professor Azar Nafisi wrote, “What we search for in fiction is not so much reality but the epiphany of truth.”13 Fiction can also deepen our capacity for empathy.14

When it came to The House of God, readers loved it; readers loathed it.15 Published in 1978, the sardonic, risqué, and poignant novel introduced irreverent slang like GOMER (Get Out of My Emergency Room), BUFF (polish to make look good) and TURF (get rid of) into medical circles.16 Author Samuel Shem, a now retired Harvard psychiatrist and pseudonym for Stephen Bergman, wrote his first-person satire of a harried intern in a busy urban hospital. It brought to light serious issues and the need for reform of intern and resident working hours and stress; medical hierarchy and its abuse; and the dangers of patient dehumanization.17 After the work was published, despite the pseudonym, Shem was outed and ostracized by much of the medical community. Years later, redemption came in the form of an invitation to give the 2009 commencement address at Harvard Medical School.18

In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, we read the story of a group of institutionalized psychiatric patients told through the eyes of long-time patient “Chief” Bromden.19 The ward is flipped upside-down with the arrival of a defiant new patient, Randle McMurphy, who faked insanity to escape a prison work farm.

The book’s patients are the protagonists, even the raucous, rebellious McMurphy; whereas the medical team, particularly Nurse Ratched, also known as “The Big Nurse,” are cast as domineering, manipulative, and callous.20

Before writing the book, author Ken Kesey had participated in a paid medical experiment to ingest psychedelic drugs and later worked as a nightshift nurse’s aide on a hospital psychiatric wing—experiences that informed his writing. 21

The book’s 1962 publication,22 and the subsequent hit-movie,23 coincided with the early process of psychiatric deinstitutionalization, which was hastened by the advent of new antipsychotic medication and funding changes.24 The novel’s powerful punch depicted how patients with serious mental illness were often stripped of dignity, warehoused, and physically and emotionally abused. It helped to broaden public awareness of the need for education, compassion, and psychiatric treatment reform.

Shaping policy

Imagine if your legacy was the result of a sample of your body tissue that was used in research without your permission, that neither you nor any of your family profited from, and yet, it helped save millions of lives. Author Rebecca Skloot wrote of such a bioethical quagmire in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, part biography, part case-study, part mystery.25

Before Henrietta Lacks died of aggressive cervical cancer in 1951, doctors at Johns Hopkins Hospital took tissue samples from her cervix. Lacks, a poor, African-American woman, neither knew nor consented to the use of her cells for research. Unlike normal cells, Henrietta’s (later known as HeLa cells) reproduced indefinitely, making them ideal for scientific research. HeLa cells have not only been used for decades in research but also for commercial gain, without any original patient consent.26

Deepening the fissure of ethical research in this case, Henrietta’s husband and children were also subsequent research subjects without their knowledge.27 This book casts a spotlight on many “slippery slope” bioethical issues involving informed consent, privacy law, racial inequity, and patient rights.28,29 It has been a model for modern biomedical ethics discussion, teaching, and reform.30

Another book, published in 2009, sparked a different type of practice reform. A decade earlier, the Institute of Medicine had released a report that reverberated through the medical community and created a call-to-action with the words, “At least 44,000 people, and perhaps as many as 98,000 people, die in hospitals each year as a result of medical errors that could have been prevented, according to estimates from two major studies.”31

In The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, surgeon and author Dr. Atul Gawande wove stories of patients, practitioners, and airplanes with data and evidence-backed science to show how the use of a simple checklist could reduce errors and save lives.32,33

Checklists have been used in aviation safety for decades.34 In fact, many of us would shudder to think of boarding a plane where the pilots skipped the pre-flight safety checklist and simply relied on their memories and a few nudging reminders from their colleagues.

It is the story of the how the introduction of a simple, 19-item, surgical checklist helped save lives and reduce complications for patients in a study that involved eight hospitals around the world.35

Since its publication, the use of healthcare checklist tools has expanded beyond the surgical version into other areas, further reducing errors and saving lives.36 The next step in the frontier may very well be checklists not only for healthcare professionals but for patients as well.37

Timing and influence

Timing matters to fairly consider a book’s impact. Sometimes a book’s seemingly brilliant insights fade into merely interesting, or conversely, the ideas shared within the pages become so well-adopted that future generations no longer view them as remarkable.

It is difficult to know which among recently published books will leave a transformational influence on future health care, although there are multiple contenders, but it is also thought-provoking to read new books through that lens and envision what changes might result.

Among the books described here, none are academic publications and yet they had a profound influence. A book’s concepts are sometimes first embraced and implemented by health professionals; whereas other times it is the general public that adopts an idea and whose passion influences the profession. An underlying theme among several of these books is that of personal (patient) education and empowerment, which by its very nature is transformative and now a goal in modern-day healthcare.38

The paradigm shifts associated with these books might have been realized without their having been published. Or, those changes might have come too late to make a major cultural impact. The worst-case scenario is that we might still be without those changes at all. Imagine then where healthcare, and we, might be today.

End Notes

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1962.

- Upton Sinclair, The Jungle. New York City: Doubleday, Jabber & Company. 1906.

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique. New York City: W.W.Norton & Company. 1963.

- Kathryn Leggit, How Has Childbirth Changed in This Century? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/explore-healing-practices/holistic-pregnancy-childbirth/how-has-childbirth-changed-century.(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Grantly Dick-Read, Childbirth without Fear. New York City: Harper-Collins. 1944.

- Grantly Dick-Read, Childbirth without Fear.

- Kathryn Leggit, How Has Childbirth Changed in This Century? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/explore-healing-practices/holistic-pregnancy-childbirth/how-has-childbirth-changed-century.(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying(New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969).

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 36.

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 51-14.

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying.

- Sherrie Dulworth, “The book that galvanized a health care transformation” Hektoen International, Winter 2019.https://hekint.org/2019/03/26/the-book-that-galvanized-a-health-care-transformation/. Accessed April 13, 2019.

- Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran.New York City: Random House. 2003.

- Julianne Chiaet, “Novel Finding: Reading Literary Fiction Improves Empathy”. Scientific American. October 4, 2013. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/novel-finding-reading-literary-fiction-improves-empathy/(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Samuel Shem, The House of God. New York City: Dell Publishing. 1978.

- Samuel Shem, The House of God.

- Howard Brody, “The House of God: Is It Pertinent 30 Years Later?”. AMA Journal of Ethics. July 2011. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/house-god-it-pertinent-30-years-later/2011-07(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Suzanne Koven,“35 Years Later, author revisits ‘House of God’,” Boston Globe. September 2, 2013. https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/health-wellness/2013/09/01/interview-with-samuel-shem/h7tS4bjDlynBYCyddW6a1O/story.html(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.New York City: Signet. 1962.

- Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

- Ken Kesey Biography. Encyclopedia of World Biography. https://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Ka-M/Kesey-Ken.html(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Film. Directed by MilošForman. Hollywood. United Artists. 1975

- Deinstitutionalization: A Psychiatric “Titanic”. PBS Frontline. May 10, 2005. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/asylums/special/excerpt.html(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York City:Crown Publishing Group. 2010

- Rebecca Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, 181-198.

- Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

- Joel Potash, “Book Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” Bioethics in Brief. Upstate Medical University. 2001. http://www.upstate.edu/bioinbrief/articles/2011/2011-03-henrietta-lacks.php. http://www.upstate.edu/bioinbrief/articles/2011/2011-03-henrietta-lacks.php. (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Rebecca Skloot Website. Teachers & Students. http://rebeccaskloot.com/the-immortal-life/teaching/(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health SystemInstitute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. National Academy of Sciences. November 1999. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto. New York City: Metropolitan Books. 2009.

- Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto.

- Philip S. Meilinger, “When the Fortress Went Down.” Airforce Magazine. October 2004. http://www.airforcemag.com/MagazineArchive/Pages/2004/October%202004/1004fortress.aspx. (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto, 153-155.

- Patient Safety Primer/Checklists. Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. January 2019. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/14/checklists(Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Asad Latif, Adil Haider, Peter Pronovost, “Smartlists for Patients: The Next Frontier for Engagement?”. NEJM Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/patient-centered-checklists-next-frontier/ (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- “Patient empowerment can lead to improvements in health-care quality.”Bulletin of the World Health Organization.95, no. 7 (July 2017): 481-544 https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/95/7/17-030717/en/(Accessed April 14, 2019).

Bibliography

- Brody, Howard. “The House of God: Is It Pertinent 30 Years Later?”. AMA Journal of Ethics. July 2011. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/house-god-it-pertinent-30-years-later/2011-07

- Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1962.

- Chiaet, Julianne. “Novel Finding: Reading Literary Fiction Improves Empathy”. Scientific American.October 4, 2013. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/novel-finding-reading-literary-fiction-improves-empathy/

- Deinstitutionalization: A Psychiatric “Titanic”. PBS Frontline. May 10, 2005. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/asylums/special/excerpt.html (Accessed April 14, 2019).

- Dick-Read, Grantly. Childbirth without Fear.New York City: Harper-Collins. 1944.

- Dulworth, Sherrie. “The book that galvanized a health care transformation” Hektoen International. Winter 2019.https://hekint.org/2019/03/26/the-book-that-galvanized-a-health-care-transformation/

- Friedan, Betty, The Feminine Mystique. New York City: W.W.Norton & Company. 1963.

- Gawande, Atul. The Checklist Manifesto. New York City: Metropolitan Books. 2009.

- Kübler-Ross, Elizabeth. On Death and Dying. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

- Leggit, Kathryn. “How Has Childbirth Changed in This Century?”. University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/explore-healing-practices/holistic-pregnancy-childbirth/how-has-childbirth-changed-century.

- Kesey, Ken. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. New York City: Signet. 1962.

- Kesey, Ken Encyclopedia of World Biography.Internet. Advameg, Inc. 2019. https://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Ka-M/Kesey-Ken.html

- Koven, Suzanne. “35 Years Later, author revisits ‘House of God’,” Boston Globe. September 2, 2013. https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/health-wellness/2013/09/01/interview-with-samuel-shem/h7tS4bjDlynBYCyddW6a1O/story.html

- Latif, Asad, Haider, Adil, Pronovost, Peter. “Smartlists for Patients: The Next Frontier for Engagement?”. NEJM Catalyst.https://catalyst.nejm.org/patient-centered-checklists-next-frontier/ http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf

- Meilinger, Philip S., “When the Fortress Went Down.” Airforce Magazine. October 2004. http://www.airforcemag.com/MagazineArchive/Pages/2004/October%202004/1004fortress.aspx.

- Nafisi, Azar. Reading Lolita in Tehran. New York City: Random House. 2003.

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Film. Directed by MilošForman. Hollywood. United Artists. 1975

- Patient empowerment can lead to improvements in health-care quality. Bulletin of the World Health Organization.95, no. 7 (July 2017): 481-544 https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/95/7/17-030717/en/

- Patient Safety Primer/Checklists. Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality.January 2019. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/14/checklists

- Potash, Joel. “Book Review: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” Bioethics in Brief.Upstate Medical University. 2001. http://www.upstate.edu/bioinbrief/articles/2011/2011-03-henrietta-lacks.php. http://www.upstate.edu/bioinbrief/articles/2011/2011-03-henrietta-lacks.php.

- Rebecca Skloot Website. Teachers & Students. http://rebeccaskloot.com/the-immortal-life/teaching/

- Shem, Samuel. The House of God. New York City: Dell Publishing. 1978.

- Sinclair, Upton, The Jungle. New York City: Doubleday, Jabber & Company. 1906.

- Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. 2010

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. National Academy of Sciences. November 1999. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf