The Book that Galvanized a Health Care Transformation

This story was first published in Hektoen International.

One of the major health care sea changes of the past half-century did not originate from the usual sources of scientific research, technological development, or even clinical trial-and-error. Instead, a book written for a general audience galvanized a health care transformation. While the cultural revolution of the 1960’s had ushered in more open talk on taboo topics like human sexuality and civil rights, talk of dying still occurred in hushed, discreet tones, and the truth of a terminal illness was often kept from the dying person. Patients, regardless of their condition or their wishes, were not often allowed to go gently into the good night.

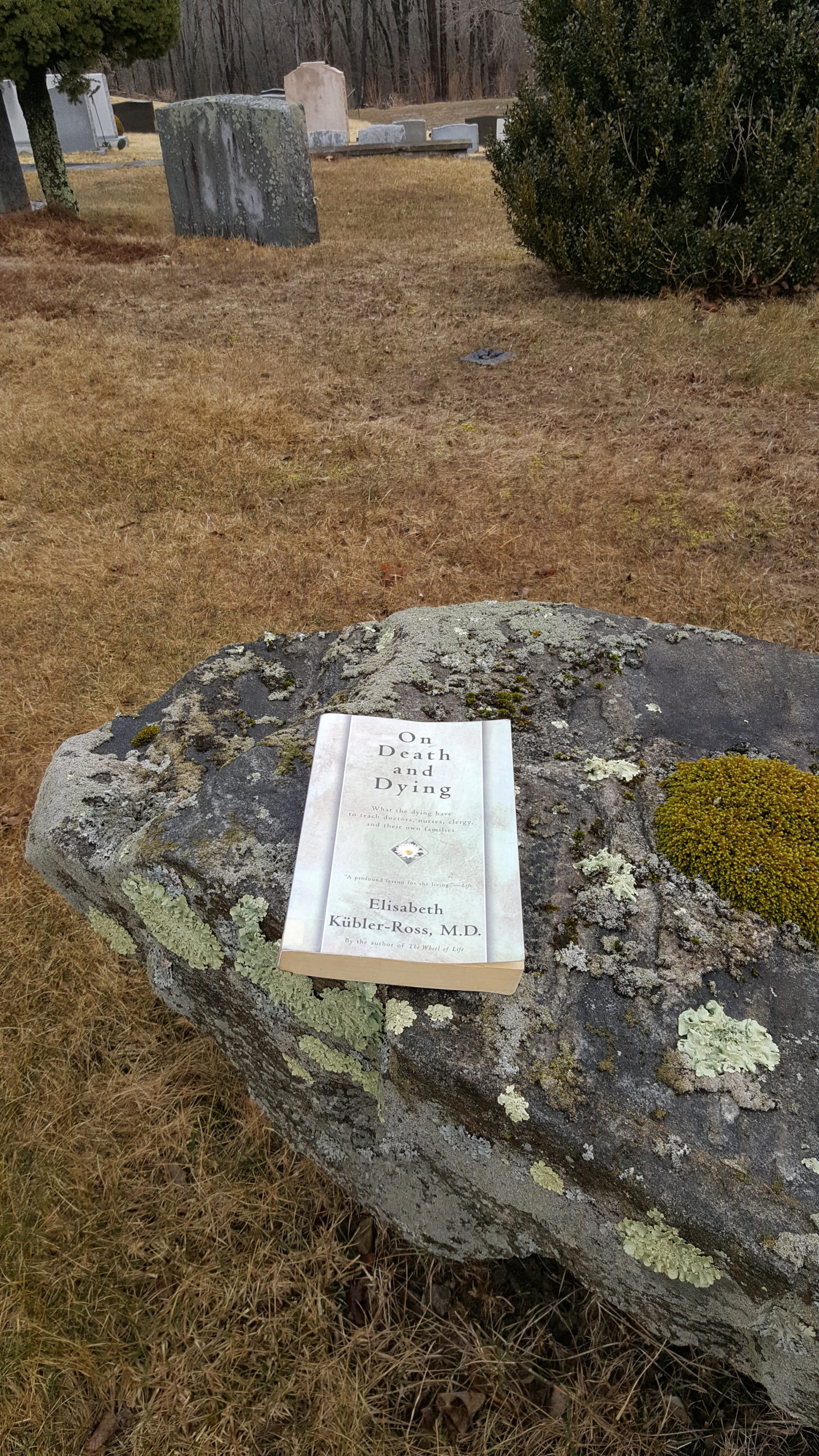

This began to change with Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and On Death and Dying.1

Cracking Open The Door

In On Death and Dying,2 the forty-two-year-old Kübler-Ross and her colleagues coalesced insights from their interviews with terminally-ill patients, families, and caregivers. While none of that may now seem groundbreaking, given the mores at the time, it was. The seminal book, published fifty years ago in 1969, cracked open the door of death’s proverbial closet.

The Swiss-American psychiatrist first sought out her fellow physicians for referrals so she could interview terminally-ill patients. She wrote, “I set out to ask physicians of different services and wards for permission to interview a terminally ill patient of theirs. The reactions were varied, from stunned looks of disbelief to rather abrupt changes of topic of conversation . . .”3 While this reluctance may have stemmed from physicians’ desire to protect their patients, the result was still resistance. Kübler-Ross noted, “It suddenly seemed that there were no dying patients in this huge hospital.”4

Fortunately, she prevailed.

Despite whatever pervasive denial there had been from others, many patients shared that they “knew” the seriousness of their condition. But intuiting the graveness of one’s condition and having a forum to acknowledge it, share feelings, and process grief, is entirely different.

The book’s publication gave rise to what has become recognized for its vital importance: patients’ rights, experience, and voice. Kübler-Ross wrote, “It is simply an account of a new and challenging opportunity to refocus on the patient as a human being, to include him in dialogues, to learn from him the strengths and weaknesses of our hospital management of the patient. We have asked him to be our teacher so that we may learn more about the final stages of life with all its anxieties, fears, and hopes.”5

Through the now famous Five Stages of Grief,6 On Death and Dying enabled us to recognize sorrow—ours and others—as a non-linear process and not a static condition. Intellectualization does not displace the emotional gut-wrench of loss, but as author Tony Schwartz wrote in The New York Times, “The answer is that naming our emotions tends to diffuse their charge and lessen the burden they create.”7

Since 1969, people worldwide have cited the phases of Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance:8 labels that in some small measure offer insight into, if not mastery of, the process of grieving. Schwartz noted, “Noticing and naming emotions gives us the chance to take a step back and make choices about what to do with them.”9

Miles To Go

On Death and Dying was the foundation for a groundswell of changes that we recognize today. Among the more prominent are hospice and palliative care programs that now offer terminally-ill patients and their families program alternatives to aggressive medical care, that can offer improved survival and a better quality of life.10,11

While varied, end-of-life and palliative training is now included in some medical school and residency curricula. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care Medicine cites a total of 138 accredited fellowship programs.12 The Hospice & Palliative Nurses Association boasts more than 11,000 members and fifty chapters in the U.S.13 All fifty states have enacted some form of legislation that helps ensure patients’ end-of-life wishes are honored.14

Those changes, and many others—like health care advocates (proxy), advanced directives, grief support groups, aid-in-dying, and public conversations shared in public forums like Death Cafes,15 and The Conversation Project16—were complete strangers in the health care vocabulary of 1969, not because we dared not utter them, but because they did not exist.

Evolution is slow; we still have miles to go in terms of how we communicate about death and dying. Case in point: research17 shows a vast discrepancy between the aggressive end-of-life treatments that doctors often prescribe for terminally-ill patients and what they choose for themselves. But we have seen a societal transformative since the time when On Death and Dying was first published.

There have now been numerous books and movies produced on this subject. This year, the very same human issues and stages of loss that Kübler-Ross wrote about were the topic of an Academy Award nominated documentary, End Game.18 This new work featured health care professionals who, instead of being entrenched in denial, facilitate honest discussions and guide patients and families in their own decision-making process.

We constantly seek the next big health care discovery or revolutionary idea; but timing matters. Even great ideas, when ahead of their time, tend to fizzle; while sometimes the next “big ideas” come from places where we least expect them. Someone must pave the way and trust that their timing will bring the lessons to life. Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross and her team laid the essential groundwork at the right time, bringing death into focus through the power of the written word.

End Notes

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969).

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying.

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 36.

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 36.

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 11

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 51-14.

- Tony Schwartz, “The Importance of Naming Your Emotions,” The New York Times, April 3, 2015,https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/04/business/dealbook/the-importance-of-naming-your-emotions.html.

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, 51-14.

- Tony Schwartz, “The Importance of Naming Your Emotions,” The New York Times, April 3, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/04/business/dealbook/the-importance-of-naming-your-emotions.html.

- Connor, Stephen R., Pyenson Bruce, Fitch, Kathryn, Spence, Carol, Iwasaki, Kosuke. “Comparing Hospice and Nonhospice Patient Survival Among Patients Who Die Within a Three-year Window.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 33 (2007):238-246. Accessed March 12, 2019. https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/JPSM/march-2007-article.pdf

- Meier, Diane E., Brawley, Otis W. “Palliative Care and Quality of Life”. J Clin Oncl. 29 (2011).: 2750–2752. Accessed March 12, 2019.10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9729

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Hospice and Palliative Care Fellowship Programs. http://aahpm.org/uploads/Program_Data_122718.pdf (accessed March 12, 2019).

- American Nurses Association and Hospice & Palliative Nurses Association Call for Palliative Care in Every Setting. https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2017-news-releases/american-nurses-association-and-hospice–palliative-nurses-association-call-for-palliative-care-in-every-setting/ (accessed March 15, 2019).

- National POLST Paradigm/State Programs/Levels of Recognition. https://polst.org/programs-in-your-state/ (accessed, March 15, 2019).

- Death Cafes. https://deathcafe.com/ (accessed March 15, 2019).

- The Conversation Project. https://theconversationproject.org/ (accessed March 15, 2019).

- Periyakoil, Vyjeyanthi S., Neri, Eric, Fong, Ann, Kramer, Helena. “Do Unto Others: Doctors’ Personal End-of-Life Resuscitation Preferences and Their Attitudes toward Advance Directives”. PLOS One. (2014). https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0098246 (accessed March 15, 2019).

- End Game. Short-documentary film. Directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. San Francisco. NetFlix. 2019.

Bibliography

- Elizabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

- Tony Schwartz, “The Importance of Naming Your Emotions,” The New York Times. April 3, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/04/business/dealbook/the-importance-of-naming-your-emotions.html.

- Connor, Stephen R., Pyenson Bruce, Fitch, Kathryn, Spence, Carol, Iwasaki, Kosuke. “Comparing Hospice and Nonhospice Patient Survival Among Patients Who Die Within a Three-year Window.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 33, no. 3 (2007):238-246. https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/JPSM/march-2007-article.pdf

- Meier, Diane E., Brawley, Otis W. “Palliative Care and Quality of Life”. J Clin Oncl. 29, no. 20 (2011).: 2750–2752. 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9729

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Hospice and Palliative Care Fellowship Programs. http://aahpm.org/uploads/Program_Data_122718.pdf

- American Nurses Association and Hospice & Palliative Nurses Association Call for Palliative Care in Every Setting. https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2017-news-releases/american-nurses-association-and-hospice–palliative-nurses-association-call-for-palliative-care-in-every-setting/

- National POLST Paradigm/State Programs/Levels of Recognition. https://polst.org/programs-in-your-state/

- Death Cafes. https://deathcafe.com/

- The Conversation Project. https://theconversationproject.org/

- Periyakoil, Vyjeyanthi S., Neri, Eric, Fong, Ann, Kramer, Helena. “Do Unto Others: Doctors’ Personal End-of-Life Resuscitation Preferences and Their Attitudes toward Advance Directives”. PLOS One. (2014). https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0098246

- End Game. Short-documentary film. Directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. San Francisco. NetFlix. 2019.